“My family lived in a segregated neighborhood in Seattle, Washington called ‘Nihonmachi’ (Japan Town) before World War II. Although I felt comfortable in my own neighborhood, when my family ventured outside, we were looked down on and endured a lot of name-calling, like ‘dirty Japs’ and ‘Nips.'”

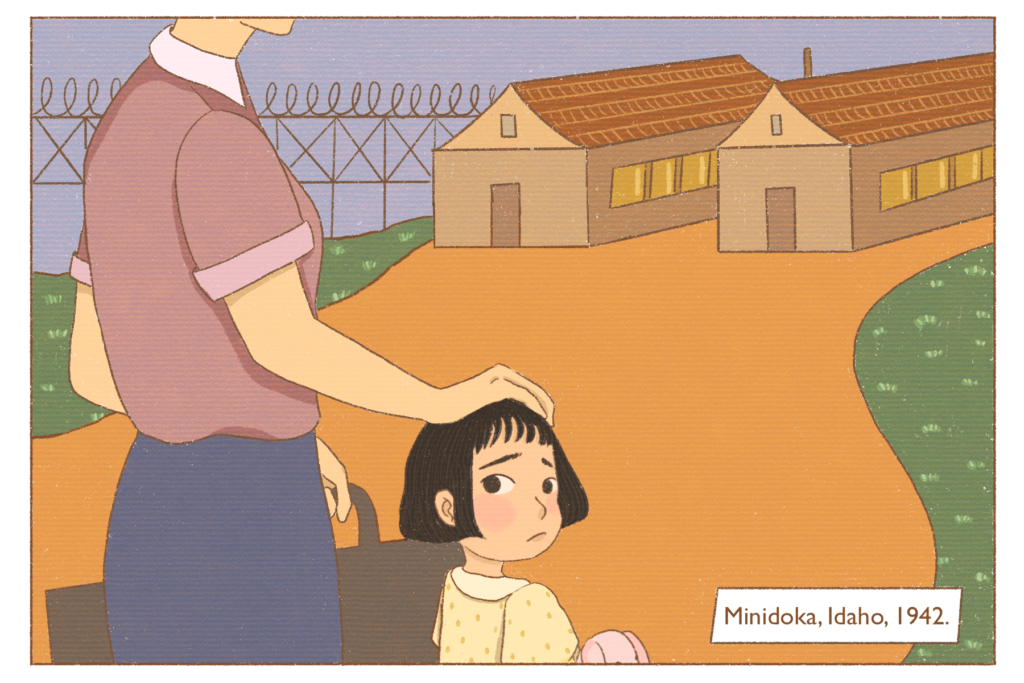

“Our lives changed forever during World War II, when my own government forcibly removed us from our home and placed us in prison camps based solely on our race. After 3 ½ years in prison, my parents lost everything they had worked for trying to make a comfortable life in America. We had nothing left in Seattle. Is it any wonder that I grew up thinking, “Is there something wrong with being Japanese?

“Learning to accept myself as a Japanese American was a long and involved process that started when I arrived in Minnesota at the age of ten directly from an American concentration camp in Minidoka, Idaho. Our family chose Minnesota because my brother was serving in the U.S. Military and trained at Fort Snelling. He found the people of Minnesota to be very friendly and accepting.

“In Minnesota I tried to be as “American” as possible, using an English name, “Sally,” instead of my Japanese name, “Shigeyo.” I was always the only Japanese, let alone person of color, in my classroom all the way from elementary school through high school. I did not congregate with other Japanese families who had also moved to Minnesota after the war. I found my friends and community in my Caucasian neighborhood.

“While studying at the University of Minnesota, I met and fell in love with a Japanese exchange student. His employer sent us to Japan to establish a branch office. A whole new chapter of my life began. I learned what a beautiful country Japan was. I loved all of its arts and crafts, and I developed a true appreciation for my culture and heritage. I was thankful to raise three children in a place where they would not have to face the same prejudice and discrimination that I knew as a child.”

“Unfortunately, my life in Japan ended abruptly when my husband died unexpectedly from a brain aneurism, but I returned to Minnesota with a new attitude about being Japanese American. I resumed my teaching career and became involved with the Twin Cities Chapter of the Japanese American Citizens League (JACL), mainly to meet others who shared a similar background with me. In 1997, our group brought the Smithsonian Institute’s photo exhibit “Whispered Silences: Japanese American Detention Camps 50 Years Later” to the downtown Minneapolis Public Library. Several of us who were survivors of the prison camps acted as docents for the exhibit, where I met many Minnesotans who had never heard about how the government established concentration camps to keep Japanese Americans confined during WWII. This opened my eyes to the need to educate the public on this chapter of American history. I began to speak at schools, churches, and community groups to tell my family’s story. I felt like I was standing up for not only the 120,000 other Japanese Americans who were victims of incarceration, but also for all of the communities in our country who have been negatively impacted by misguided government policies.

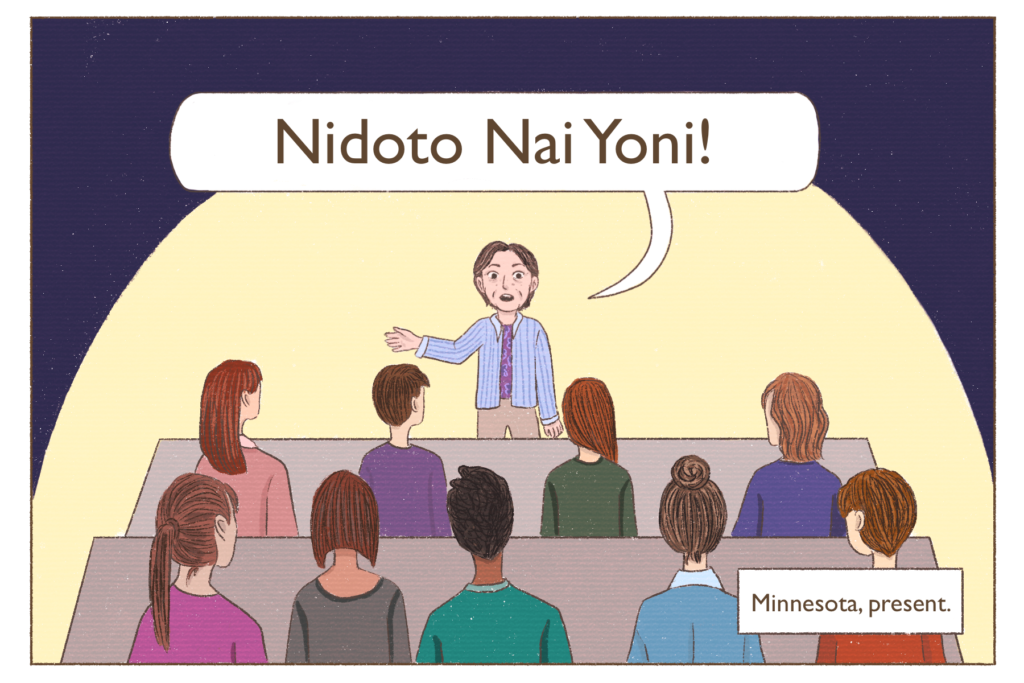

“In the past 25 years of my retirement, I have made it my mission to emphasize the importance of speaking up whenever we see injustice, and help my neighbors realize how easily our civil liberties can be taken away if we are not vigilant. We cannot be bystanders, because if we remain silent we are condoning the injustice. Our JACL rallying cry is, “Nidoto nai yoni” — NEVER AGAIN!”